The streets we walk and the streets we don't

When we campaign to change our streets are we focussing on the right things if we aren't listening to the people who live there?

Fatima Durrani, our Project Support Coordinator at Living Streets Scotland, tells us how she's starting conversations with people to find out what matters to them and the changes they want to see.

I often find myself wondering what purpose training sessions, reports and social media posts serve if a South Asian woman who has lived and worked in this city her whole life hesitates to head out for her doctor-mandated daily walk because there is no place for her to sit if she gets tired midway. Because she has been told off by her neighbours before for needing to catch a breath perched on their wall.

I have come to realise that words and efforts are meaningless unless we find a way to bridge the gap between the words and the people who can benefit from them.

Kate Joester, Projects Team Leader for Scotland Living Streets, and I have begun to bridge that gap through our project, Boosting Walking Policy. We are working to promote walking and wheeling in Scotland to support community and individual health while enabling decision makers to engage with communities in a meaningful way, to listen to people and give them that sense of ownership so they can be part of the whole process of change

For my part, I wanted to bring my lived experience and my knowledge in this area to offer a conversation within the community to learn more. I am super brown and possibly the most passionate person I know about walking. So I was delighted to find myself outside the front door of Glendale Women’s Café, a community space built to uplift local women, on a grey afternoon in Pollokshields East, Glasgow.

I was looking forward to facilitating a workshop on belonging and walking with a group of South Asian women who live in the area and frequent this café for communal lunch, companionship and the events that this amazing space hosts. I was delighted to be working with South Asian women in particular – a community that is statistically among the least represented in walking culture in Scotland.

Living Streets was there to gain insights from one of the most vulnerable minority groups in the UK about their experiences with walking and to incorporate these findings into our vital policy work. This ensures that our work remains inclusive and diverse. This is an example of how a well-bridged gap can create meaningful impact.

So here I am, waiting for the café doors to open, mentally reciting everything I’m supposed to talk about —

“How did you arrive at the café today?”

“What do you think about your neighbourhood?”

“What motivates you to walk?”

"Proper walking infrastructure is vital for improving the physical and mental well-being of every Scottish individual, but it’s of particular importance for Scottish-South Asian women."

Then along come a big, colourfully dressed, laughing and chatting group of South Asian women. They spot me waiting outside, and I say my Salaams to them. They greet me, ask how long I’ve been waiting, and why I’m here today. I tell them, and they seem super excited.

A fantastic start to the day, I think.

Until I realise, I haven’t spoken a single word of English in this entire exchange so far. Nor are any of the ladies speaking English amongst themselves.

That’s perfectly fine, though, I tell myself. I can very comfortably switch between English and Urdu when I conduct the session, and I understand a fair bit of Punjabi (which most of the ladies are speaking), so it should all be fine.

Except, all the rehearsals in my mind had been in English and suddenly, the prospect of switching from:

“What motivates you to walk?” to “Aap ko chalne ke liye kya hausla afzaai karta hai?” sounds strange because the Urdu version of my English question is ludicrous.

In Urdu, I don’t think of walking as something that must be carried out with a specific goal. Walking is not a mere verb; in Urdu, walking is chehal-qadmi — it’s leisurely, it’s an act saved for and savoured under the moonlight when the wind blows, and the sun isn’t suffocating you. It’s a couple holding hands and strolling in an unkempt park. It’s dilly-dallying. And it’s sacred – because South Asian cities are unwalkable to their core, so when you do walk, it must be somewhere beautiful and worth the effort.

Using the Urdu translation for walking in a question about a very non-Urdu version of walking feels absurd.

I suddenly feel terribly unprepared for today.

I shouldn’t be feeling this nervous about having to talk about something I’m passionate about in my national language, but alas, the chokehold that the language of the coloniser has on me — I do not use the word chehal-qadmi even once in the 1.5-hour-long session. I stick to using walking.

Our session covered a range of issues including discussions about what is a barrier or facilitator to walking, and of course, lots of food and a cacophony of Scottish-English, Urdu and Punjabi.

All of the women had incredibly valuable insights to offer, and some in particular stood out for me.

Many women spoke about the importance of pedestrian-friendly infrastructure with one of the participants sharing: “I would walk longer distances if there were public toilets. No public toilets mean I can’t carry along my water bottle. No water bottle means I don’t drink water, and because I tend to get quite thirsty — I’d rather just drive the distance instead.”

Another woman shared: “We don’t walk because we are lazy. We just need to stop being lazy and get out more.”

This stopped me in my tracks. I wanted to talk to them about the significant structural barriers that prevent walking from being easy and accessible to them. I wanted to tell them you are not lazy, my dear, beautiful, fellow brown woman. You are overworked because of all the full-time jobs you do for your family. You are not lazy. You have been systematically stripped of the time and energy required to embark on the daily meagre 3,000 steps needed to significantly reduce your blood pressure.

Another issue that emerged as we spoke was of the women’s experience of the culture of our walking environment and the people we share it with. In Islam, dog saliva is considered impure. Thus, a lot of the ladies at the session were very vocal when the topic of dog encounters on their walks came up.

“They think we don’t like their dogs. We do like dogs! Just not when they lick us or come up to us. Sometimes I avoid parks where I know there will be a lot of dogs because if a dog licks me as I am walking, I know that I will have to go back home and change my clothes.”

Even the quietest of the workshop participants had something to add and the consensus was unanimous: properly trained and leashed dogs make a huge difference when it comes to deciding where to walk and where not to, and they can sometimes avoid beautiful parks because of worries around how untrained dogs may behave there.

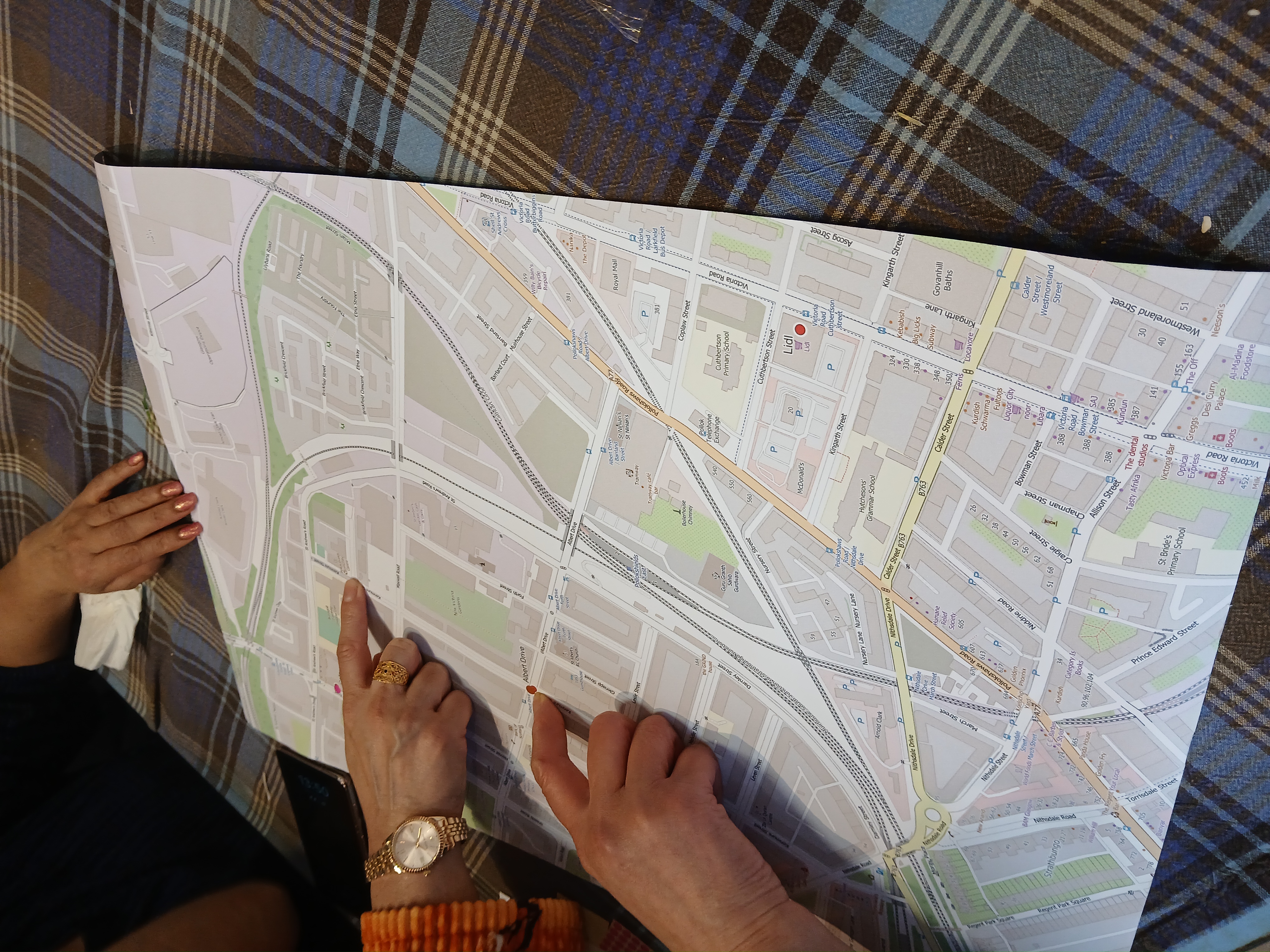

The importance of having a sense of belonging was underscored throughout the entire session. When looking over maps of their local area and marking out places they love, like, dislike and avoid, the first thing one participant did was make a beeline straight to finding her house to orient herself in the area.

There was so much that I learned from these amazing women and the time I spent with them. One thing was abundantly clear: that proper walking infrastructure is vital for improving the physical and mental well-being of every Scottish individual. But it’s of particular importance for Scottish-South Asian women who are not only financially disenfranchised but have been carefully hushed away into specific neighbourhoods by town planners and politicians. They tread the same well-worn paths between the supermarket, that one Asian grocery store, that one school, and that one mosque — never straying beyond, into the wider, greener spaces that should be theirs to claim, to explore, and to own.

This event and others planned later this year are about creating manifestos for change with communities to drive action by local decision makers. We are grateful for funding from Paths For All and European Climate Foundation to be able to centre the work of communities in our engagement and campaigning approach.

If you would like to start a group to lead walks locally and host conversations like this then find out how on our Local Groups page.

About the author

Living Streets